- Home

- Directory

- Shop

- Underwater Cameras - Photographic Accessories

- Smartphone Housings

- Sea Scooters

- Hookah Dive Systems

- Underwater Metal Detectors

- Dive Gear

- Dive Accessories

- Diving DVD & Blu-Ray Discs

- Diving Books

- Underwater Drones

- Drones

- Subscriptions - Magazines

- Protective Cases

- Corrective Lenses

- Dive Wear

- Underwater Membership

- Assistive Technology - NDIS

- On Sale

- Underwater Gift Cards

- Underwater Art

- Power Stations

- Underwater Bargain Bin

- Brands

- 10bar

- AOI

- AquaTech

- AxisGo

- Backscatter Underwater Video and Photo

- BLU3

- Cayago

- Chasing

- Cinebags

- Digipower

- DJI

- Dyron

- Edge Smart Drive

- Eneloop

- Energizer

- Exotech Innovations

- Fantasea

- Fotocore

- Garmin

- Geneinno

- GoPro

- Hagul

- Hydro Sapiens

- Hydrotac

- Ikelite

- Indigo Industries

- Inon

- Insta360

- Intova

- Isotta Housings

- Jobe

- JOBY

- Kraken Sports

- LEFEET

- Mirage Dive

- Nautica Seascooters

- Nautilus Lifeline

- NautiSmart

- Nitecore

- Nokta Makro

- Oceanic

- Olympus

- OM System

- Orca Torch

- Paralenz

- PowerDive

- QYSEA

- Scubajet

- Scubalamp

- Sea & Sea

- SeaDoo Seascooter

- SeaLife

- Seavu

- Shark Shield

- Sherwood Scuba

- Spare Air

- StickTite

- Sublue

- Suunto

- SwellPro

- T-HOUSING

- Tusa

- U.N Photographics

- Venture Heat

- XTAR

- Yamaha Seascooter

- Youcan Robot

If Looks Could Kill

Contributed by Scuba Diver Australasia

If looks could kill, the whale shark would be the most deadly creature in the sea. Up to 14 metres in length, weighing as much as 20 tonnes, and sporting hundreds of teeth, it is outclassed in size only by the true whales. But Rhincodon typus, as it is known to marine biologists, feeds low on the food chain. Its teeth are tiny and its diet consists of planktonic crustaceans, fish eggs, coral spawn, jellyfish, small schooling fishes, squids, and the occasional tuna. Other than the rare collision with a boat, it poses no threat to humans, and has become one of the most prized living destinations for underwater tourists around the world.

Perhaps because their appearance belies their gentle behavior, the sight of

whale sharks feeding has captivated divers for decades. Instead of passively

filtering planktonic animals from the water column, as is the habit of similarly

sized whales and its cousin the basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus),

whale sharks migrate around the world’s tropical waters, actively seeking

out and sucking in their tiny prey. A cavernous mouth located at the front of

the head, rather than slung beneath, is large enough to swallow two humans simultaneously.

As it swims to the surface, muscles in the mouth create a powerful vacuum effect

then close on their target. Modified gill rakers act like a sieve, seawater

is expelled through the gills, and food finds its way into the stomach.

Accidents can happen, of course. But when a whale shark swallows something too

large to digest – say a large fish or market buoy – it can cough

up the unwanted meal by forcing its stomach up its throat in a process called

gastric inversion. Other curious evolutionary adaptations include a checkerboard

pattern of light spots and stripes on a dark background covering its back. Scientists

suspect the coloring developed as protection from the ultraviolet radiation

to which the sharks, which spend a large amount of time feeding near the surface,

are exposed.

While the whale shark does not prey on humans, the reverse is not the case.

Hundreds are taken each year by directed fisheries and as incidental bycatch

in tropical and subtropical oceans around the world. The flesh is the most valuable

product, with fisheries in India and Philippines driven by demand from Taiwan,

where whale shark meat fetches between US$2 and $7 a kilogram - and there is

a lot of meat on a 20-tonne shark. Like many other shark species, its fins are

also prized by Asian restaurants serving shark-fin soup. A single large whale

shark fin can sell for thousands of dollars, though due to its lower quality,

most are used as decorative signage for retailers and restaurants dealing in

the fins of other species.

Demand is growing, catches are already falling and some populations appear to

have been seriously depleted, according to the IUCN - World Conservation Union.

Fortunately, whale sharks recently joined a list of species managed by the Convention

on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

The 'Appendix II' listing means the 166 member countries of CITES must certify

that any exports of whale shark products will not harm wild populations.

The campaign to add R. typus to the list was not an easy one. A proposal

to add whale sharks was defeated in 2000. A second attempt, co-sponsored by

the Philippines (where the species is already fully protected) and India, came

just two votes short of passing during an initial discussion at the 2002 CITES

meeting. The primary opposition came from member nations resistant to the idea

of using CITES to regulate the trade in marine fishes in the first place. But

later in the same meeting, following a presentation by Project Seahorse, CITES

members agreed to list all species of seahorses on Appendix II, and the precedent

of including a commercially valuable species of marine fish had been set. Proposals

to list both the whale and basking sharks then returned to the table and passed

by slim margins.

While seahorses, among the smallest fishes, may have paved the way for the protection

of the largest, much of the support for the listings can be attributed to powerful

arguments about the economic importance of whale shark ecotourism in developing

countries. The task of securing a future for whale sharks is far from complete,

but continued support from the diving community will go a long toward ensuring

their survival.

James Hrynyshyn,

Biologist & communications

coordinator with Project Seahorse

www.projectseahorse.org

Rogest Research Team: www.rogest.com

Project Seahorse is an international marine conservation organization that

conducts scientific research, establishes marine protected areas, advances environmental

education and works to restructure global trade. More information is available

at www.projectseahorse.org.

This article was originally published in Scubadiver Australasia

Shopfront

-

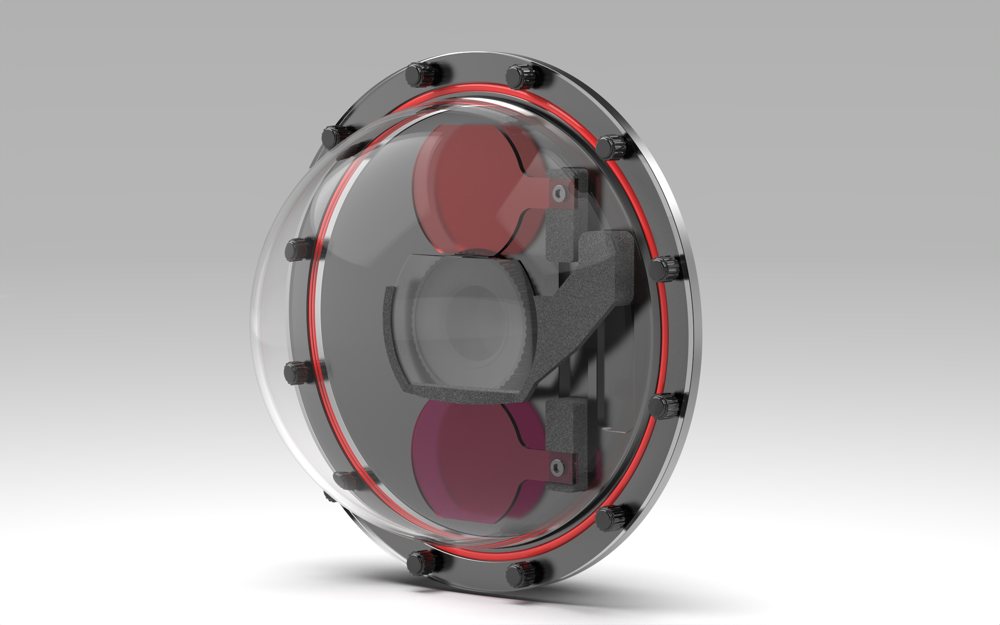

T-Housing DOME1 Aluminium Housing for Insta360 ONE R 1-inch

T-Housing DOME1 Aluminium Housing for Insta360 ONE R 1-inch

- Price A$ 499.00

-

AOI UH-EM1III Underwater Housing for Olympus OM-D E-M1 II & III

AOI UH-EM1III Underwater Housing for Olympus OM-D E-M1 II & III

- Price A$ 1,699.00

-

SeaLife Sea Dragon 3000SF Pro Dual Beam Photo-Video light

SeaLife Sea Dragon 3000SF Pro Dual Beam Photo-Video light

- Price A$ 949.00

-

Nitescuba Float Block FAXS/FAXM

Nitescuba Float Block FAXS/FAXM

- Price A$ 59.95

-

Nautica J-Class Seascooter

Nautica J-Class Seascooter

- Price A$ 1,499.00

In the Directory

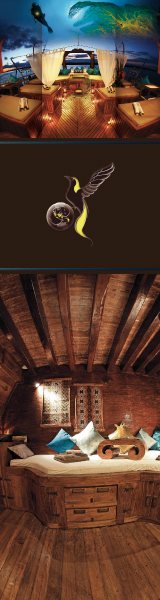

Wakatobi Dive Resort

Wakatobi Dive Resort

Wakatobi Dive Resort has some of the most pristine reefs in Indonesia at its doorstep. Protected by their Collaborative Reef Conservation Program, Wakatobi is the #1 choice for sophisticated divers.

Pelagian Dive Yacht

Pelagian Dive Yacht

Feel like you're on a private yacht charter with just ten guests. Pelagian cruises the outer reaches of the exquisite Wakatobi region.

Dual Beam Video Light Package with tray and arms - 4000 lumens - Scubalamp PV21 x 2

Dual Beam Video Light Package with tray and arms - 4000 lumens - Scubalamp PV21 x 2  Sealife Super Macro Close-Up Lens for Micro HD / 2.0 / 3.0 and RM4K

Sealife Super Macro Close-Up Lens for Micro HD / 2.0 / 3.0 and RM4K