- Home

- Directory

- Shop

- Underwater Cameras - Photographic Accessories

- Smartphone Housings

- Sea Scooters

- Hookah Dive Systems

- Underwater Metal Detectors

- Dive Gear

- Dive Accessories

- Diving DVD & Blu-Ray Discs

- Diving Books

- Underwater Drones

- Drones

- Subscriptions - Magazines

- Protective Cases

- Corrective Lenses

- Dive Wear

- Underwater Membership

- Assistive Technology - NDIS

- On Sale

- Underwater Gift Cards

- Underwater Art

- Power Stations

- Underwater Bargain Bin

- Brands

- 10bar

- AOI

- AquaTech

- AxisGo

- Backscatter Underwater Video and Photo

- BLU3

- Cayago

- Chasing

- Cinebags

- Digipower

- DJI

- Dyron

- Edge Smart Drive

- Eneloop

- Energizer

- Exotech Innovations

- Fantasea

- Fotocore

- Garmin

- Geneinno

- GoPro

- Hagul

- Hydro Sapiens

- Hydrotac

- Ikelite

- Indigo Industries

- Inon

- Insta360

- Intova

- Isotta Housings

- Jobe

- JOBY

- Kraken Sports

- LEFEET

- Mirage Dive

- Nautica Seascooters

- Nautilus Lifeline

- NautiSmart

- Nitecore

- Nokta Makro

- Oceanic

- Olympus

- OM System

- Orca Torch

- Paralenz

- PowerDive

- QYSEA

- Scubajet

- Scubalamp

- Sea & Sea

- SeaDoo Seascooter

- SeaLife

- Seavu

- Shark Shield

- Sherwood Scuba

- Spare Air

- StickTite

- Sublue

- Suunto

- SwellPro

- T-HOUSING

- Tusa

- U.N Photographics

- Venture Heat

- XTAR

- Yamaha Seascooter

- Youcan Robot

Southern exposure - Commercial diver training in New Zealand

Contributed by Simon

This

article will hopefully be of interest to divers considering a career in commercial

diving or wishing to complete a commercial course for other reasons. Hopefully

it will give you a bit of an insight into what to expect. Especially if you

plan to do the course in New Zealand (only one training agency there - New Zealand

School of Commercial Diver Training). Others may just be interested out of morbid

curiosity, what's commercial diving all about?

This

article will hopefully be of interest to divers considering a career in commercial

diving or wishing to complete a commercial course for other reasons. Hopefully

it will give you a bit of an insight into what to expect. Especially if you

plan to do the course in New Zealand (only one training agency there - New Zealand

School of Commercial Diver Training). Others may just be interested out of morbid

curiosity, what's commercial diving all about?

As someone already trained and working as a scientific diver I probably came at the course from a different angle than most people. For me, the course was a requirement so I could continue to act in the role of Diving Officer at my place of work (Southern Cross University). I feel this gave me a somewhat different perspective than most people on the course in that I didn't really want to work as a construction diver.

Most divers on the course I participated in seemed to aspire to a career in the on-shore or particularly the lucrative off-shore dive industry (where salaries can range up to several thousand dollars a day). Also, studying in a different country and with little time I was particularly focused on getting through the course material and finishing everything I needed to for the qualification. Most of the other course participants were there for the long hall, aiming to finish up to ADAS (Australian Diver Accreditation Scheme) level 3.

Why do ADAS level 1?

In 1999 Standards Australia released a standard for occupational diving AS2299.1 and shortly after a standard for diver training AS2815. These standards apply to construction divers (people working off-shore on oil rigs and on-shore doing vessel hull inspections, construction work and soforth). AS2815 specifies training requirements for everything from SCUBA diving to 30 metres (ADAS level 1), to surface supply to 30 (level 2) and 50 metres (level 3) and beyond to saturation diving (where divers live and work at pressure for extended periods of time). Most construction work on-shore is done on surface supply, so people wishing to work in this area usually need to be qualified up to level 2. This course also provides training in pneumatic tools, welding and other skills needed by construction divers. In level 1 only basic hand tools are used (like wood and metal saws, chisels, spanners, lift bags, cameras and basic survey tools).

The level 1 course is the first step in a long and expensive road culminating

in increasingly higher pay packets. Deservedly so in what is reputedly the second

most dangerous profession. A profession that, in the past particularly, can

leave participants with significant long term health problems.

Generally these standards do not directly relate to scientific divers like me

(although level 1 is considered an entry level commercial qualification suitable

for scientific diving and similar professional work using SCUBA). Of more relevance

to universities and research centres is AS2299.2, which came out in 2002. This

standard applies specifically to scientific diving and is the benchmark that

we are expected to apply in all our diving operations (along with relevant Workcover

guidelines). Failure to do so could result in massive fines for individuals

and organisations.

Although there are other routes to qualify as a scientific diver under AS2299.2, the Diving Officer for an institution (me) must be trained to the equivalent of AS2815.1 (ADAS level 1, level 2 if overseeing surface supply but we don't do that). Other scientific divers can be qualified with cheaper and more specialised courses (some run through ADAS - controversy exists about the validity of other ways to achieve competency under the standard).

Why NZ?

Originally I had tried to get in on a course in Australia. Unfortunately, due to the off-shore diving boom after Hurricane Katrina and other factors there is a high demand for off-shore divers, they would only accept students wanting to do up to ADAS level 3. Despite applying early enough the course filled up and I missed out.

I could have gotten on to a course later in the year but didn't think my colleague would be too happy if I left him with a bunch of marking at that time. There was a course on offer in New Zealand starting in late July (mid winter). Overall I think the entire trip would have cost around $8000 with the course costing me about $4500 alone (be aware most prices in Australia at least will go up significantly next year). ADAS level 1 is internationally recognised.

Shack by the lake

My first impressions of Huntly (where I was based for the duration of the course) were not that encouraging. Huntly is a mining town and there is a large coal fired power station that dominates the landscape. On the outskirts of town the bus I was in was passed by a ute with a wild boar strapped to the roof. New Zealand I was told (at least away from the major cities) is very much "frontier country", with hunting and fishing major pass times. Our principal instructor loved to share his hunting exploits during quite times and every dive shop is stocked with gear to catch "crays" and abalone (I'm not used to divers being able to take anything).

This

photograph shows my cabin by the lake. The blue bag is my cool bag for fruit,

veg and milk. In the first few days the air temperature outside the cabin was

actually colder than the fridge in the camp kitchen...

This

photograph shows my cabin by the lake. The blue bag is my cool bag for fruit,

veg and milk. In the first few days the air temperature outside the cabin was

actually colder than the fridge in the camp kitchen...

The camp site facilities were basic but the locals (at least in the camp) were friendly, if a bit rough around the edges. Because I had so much dive gear to carry I didn't have any bedding. Nor did I have any food for the first night. One of the instructors kindly offered me his lunch/dinner and the camp owners came through with a sleeping bag and a heater. A couple of trips to nearby Hamilton with other guys from the course over the next few days secured sheets, towels and cutlery for the duration.

I met most of the other students on the first night and following morning. There were eleven of us completing level 1 from start to finish and three divers who arrived about two weeks into the course to complete it by RPL (Recognition of Prior Learning - in other words people who already worked in the commercial industry and just needed certification).

We had quite a mix of participants on the course with several ex-navy guys, people working in the recreational dive industry and a few guys who had only recently got into diving or had dived mostly for recreation or finding a meal. All guys, apparently they do occasionally have ladies doing the course but given some of the antics on the course I'm not sure how that would play out (by tradition the last night is spent in a very "scanky" strip joint in Hamilton, for example).

There was a lot of colourful language and banter (apparently you need to "harden up" to work in the commercial industry) and a couple of robust personalities, but I count myself fortunate to have had such a great bunch of people to do the course with. Apparently divers have a pretty poor reputation around Huntly and Hamilton, being banned from many reputable (and not so reputable) establishments. On the first night the police came around and recorded all the number plates of the divers cars and apparently divers have a lot of street cred as an earlier crew burnt down the club house belonging to a local gang.

In mid winter Huntly is a very windy and wet place. Andrew, who shared the cabin with me for the first couple of weeks, explained that being such a narrow strip of land New Zealand doesn't usually hold weather. The adage "if you don't like the weather, wait five minutes" is disturbingly accurate (as is the Crowded House song "Four seasons in one day" which I had a lot of trouble getting out of my head for the duration - as a side note Huntly is not that far from Ti-Awamutu, another song to try and get out of my head).

I dried all my gear each night with a heater in the cabin as there was rarely more than an hour of sun, "occasional showers" was pretty much a given. The ground was constantly wet and keeping cloths, dry-suit thermals and bedding dry was a priority. One of the reasons I chose the cabin I did (on advice) was because it received more sun than some of the cabins and consequently stayed dryer.

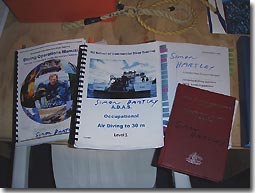

Some light reading

Although the theory component of the course was not that far removed from recreational diving you had to know the material inside and out. There were five exams in total and most questions were short answer (no multiple choice). I thought we would do an exam a week but we ended up doing all the exams over two days which was pretty tough going. There were exams on diving physiology and medicine, using the tables, physics and calculations (calculating lift, suction, gas required, etc), equipment and a final three hour exam combining all these topics.

Study

material provided included; the Australian Standard for commercial diving (AS2299.1),

a diving operations manual and a study guide covering all the topics we were

assessed on plus the theory component for practical exercises. Some of the topics

in the study guide included such things as; an introduction to occupational

diving and AS2299.1, diving physics (gas laws principally), anatomy and physiology,

diving maladies, dangerous marine life (pretty much all Australian), equipment

(everything from how different regulators work to compressors), dive procedures,

how to use the DCIEM tables, calculations for commercial divers, use of tools,

rigging and underwater search patterns.

Study

material provided included; the Australian Standard for commercial diving (AS2299.1),

a diving operations manual and a study guide covering all the topics we were

assessed on plus the theory component for practical exercises. Some of the topics

in the study guide included such things as; an introduction to occupational

diving and AS2299.1, diving physics (gas laws principally), anatomy and physiology,

diving maladies, dangerous marine life (pretty much all Australian), equipment

(everything from how different regulators work to compressors), dive procedures,

how to use the DCIEM tables, calculations for commercial divers, use of tools,

rigging and underwater search patterns.

For the first few weeks of the course I was studying till 11.30 each night

and on weekends in my cabin/drying oven...

I would recommend anyone contemplating a commercial course get hold of the study

guide and other material well ahead of time. It's a lot to absorb during the

course. It would also help to familiarise yourself with the DCIEM tables and

the rules for using these tables (eg. the rules for repetitive divings). Fortunately

I had a bit of a head start as we are required to use the Canadian tables for

our work dives.

The class room work was a bit disjointed at times I felt but the instructors certainly new their stuff and were well versed in the material. Basically the lectures covered pretty much what was in the book and important material was highlighted and revised. I found it helpful to mark all the highlighted material with small post-it notes to find it easily and study for the exams. Much of the material needed to be rote learnt; anatomical features, signs and symptoms for various maladies, equipment schematics and so forth. There were around 20 sets of review questions in the notes that needed to be completed and these were very similar to the exam questions.

Caffeine and other popular drugs

I often don't sleep well at the best of times and add a fair bit of stress and a different bed and diet and you can imagine I did not fare well for the duration. I hate coffee so energy drinks were the order of the day when I needed to function. However, I stuck to my guns on another front and kept away from the other mainstream drug of choice that was popular when there was a break or during the end of course festivities.

Early

on we were all advised to visit the chemist and buy some ear drops to stave

off ear infections in the cold, wet conditions. Other drugs got added to the

mix later. I brought some herbal tablets from OZ to help keep colds and flu

at bay and a bad experience on one of the dives caused me some ear pain prompting

me to use a decongestant spray to make sure this didn't happen again.

Early

on we were all advised to visit the chemist and buy some ear drops to stave

off ear infections in the cold, wet conditions. Other drugs got added to the

mix later. I brought some herbal tablets from OZ to help keep colds and flu

at bay and a bad experience on one of the dives caused me some ear pain prompting

me to use a decongestant spray to make sure this didn't happen again.

Add all this up and include the very limited range of culinary options in Huntly (there were four chinese takeaways, none of which appeared to sell anything resembling actual chinese food, and not much else) and I felt in serious need of "detoxing" by the time I got back to Auckland at the end of the trip. My last days in NZ were in an expensive hotel in the city centre stuffing myself silly on gourmet food, stuff the budget.

The photograph on the right shows what I took to keep diving. Vosol was to protect against ear infections in the cold, fresh water lake. Otrivine is a steroid nasal spray to open up the eustacian tubes (started taking on advice from one of the RPL guys after one dive when I hurt my ears a bit), Thoat-Clear was to stave off colds and the V was a substitute for sleep. I'd show you what I looked like after a week and a half without much sleep (start of course) but it's not pretty...

Dressed for success

One of my pet hates in diving is flimsy, plastic, poorly designed equipment and accessories commonly sold in most dive shops. I think in diving you need to be able to rely on your gear and there's no excuse for flimsy, cheaply made gear. There are few enough chances to get out and enjoy the underwater world without some silly problem stopping you diving. Your enjoyment, work sometimes and occasionally survival depends on your dive gear. Worth then taking a bit of time, and maybe extra expense, to get solid reliable gear.

The dive gear used by commercial divers (at least at this level) has some commonality with recreational dive gear and some notable differences. For recreational and scientific diving I use either a double or single tank DIR style equipment configuration. I was please to discover that a stainless backplate with one piece harness and single tank wing seemed to be pretty much the standard for commercial diving in NZ. My Scubapro jet fins and stainless straps were also embraced warmly (commercial divers seem to have a similar philosophy to me in that gear needs to be tough and reliable, no silly rubber straps or cheap plastic clips to break - time is money and you have to be able to rely on your gear).

However, that's pretty much where the similarity ends. Commercial diving is a different paradigm and the different approach to diving is reflected in equipment choices and how that equipment is configured and used.

In most recreational diving (and I use the term broadly to encompass technical and cave diving as well) divers are relatively autonomous underwater and need to be self sufficient and able to deal with problems when they arise. Consequently the buddy system (extend this to three man team where applicable) has evolved where by divers render assistance to one another should a problem arise during the dive. Assisting in an out of air being the most critical role for a buddy. Equipment and procedures in recreational diving are set up around this autonomous free swimming paradigm (obviously I think the DIR system is the ultimate expression of this paradigm but that argument is for another time).

In commercial diving however the biggest difference is that the diver is physically connected to the surface by a shot line. In most cases the diver also has continuous contact with the surface through voice communication ("comms"). The divers shot line is tended so line can be let out or taken in as needed. The diver has a redundant air supply and a safety diver is fully kited up and standing by on the surface should a problem arise.

Should a problem arise the commercial diver can be immediately located (by following his/her shot line). You will notice the dive gear pictured below has no "octopus" regulators (or no long hoses to facilitate air sharing underwater). The diver or team of divers is not autonomous, rather if there is a problem the diver either switches to a bailout and exits the water, is pulled up to the surface by their tender or the standby diver is sent in (following the divers shot line) to perform a rescue.

The gear pictured below is not that well laid out but the RPL guys were meticulous

about reducing clutter and making all the hoses and lines slick to avoid entanglement.

There are a lot of entanglement hazards in commercial diving and the slicker

your gear the better.

Arthur (another RPL guy) showed me some nice pictures of guys rigged for surface

supply work. Very slick (all hoses and lines were kept close to the body and

secured to avoid entanglement).

Another

of my pet hates in recreational (and scientific) diving is cluttered, messy

equipment layouts. Having cluttered gear; reduces response time in an emergency

or in finding critical bits of kit like inflators or weight belt releases, creates

drag, creates unnecessary entanglement hazards and just makes a diver look sloppy

and uncoordinated. Worse, if this sloppy attitude is carried forward into more

challenging diving (cave and technical diving for example), as is more and more

often the case, the consequences can be far more serious.

Another

of my pet hates in recreational (and scientific) diving is cluttered, messy

equipment layouts. Having cluttered gear; reduces response time in an emergency

or in finding critical bits of kit like inflators or weight belt releases, creates

drag, creates unnecessary entanglement hazards and just makes a diver look sloppy

and uncoordinated. Worse, if this sloppy attitude is carried forward into more

challenging diving (cave and technical diving for example), as is more and more

often the case, the consequences can be far more serious.

Prior to every dive a detailed pre-dive check is conducted where-by the supervisor runs through the divers equipment with each diver and their tender and performs gas shutdowns and switches and comms checks. Divers must all have knives suitable for cutting through thick umbilical lines and these knives must be immediately accessible. Divers must also locate shot lines (and check they're secure), weight belt releases, inflators, purge masks and perform other checks. All tank pressures (including ponys, stand-by divers and O2 cylinders) and dive start and end times are meticulously recorded on the myriad of check lists and dive sheets.

Several

of the equipment configurations used during the course are pictured here. The

first two setups show AGA/Interspiro Divator MK II full face masks with either

a belt block or inverted pony (move your cursor over the images for further

details). These were the setups we used most often during the course...

Several

of the equipment configurations used during the course are pictured here. The

first two setups show AGA/Interspiro Divator MK II full face masks with either

a belt block or inverted pony (move your cursor over the images for further

details). These were the setups we used most often during the course...

We used a Scubapro FFM with belt block but no photo's (I have one of these at home). They are reasonably comfortable but by separating nose and mouth they create problems with fogging and I found it hard to make myself understood over comms with this mask. I also find the fitting for installing a mouth piece inside the mask gets in my way when I try to talk.

Favorite setup? Hmm... probably an AGA with an inverted pony is the slickest

but if setup right (custom length hoses to reduce clutter) I reckon an AGA with

a belt block would be the best/safest option. Either way the AGA (once I got

used to it) was by far my favourite mask. I can see why they are so popular

in the industry.

The Kirby Morgan Exo is shown here on the left, a great mask (if you don't mind salt water aspiration). Some people loved them some people hated them but everyone agreed they breathed wet. I liked the mask first time I used it but second time round it fogged badly and this in part contributed to some erratic depth changes that hurt my one ear a bit. After that I dove with fins on every dive (so I had a bit more control) and made sure the mask was properly defogged...

Make no mistake however, a full face mask (particularly with comms) is noisy, very buoyant (annoying) and claustrophobic at times (on the surface in particular). I found it very disconcerting that I couldn't just take my mask off or reg out whenever I felt like it. On the surface or underwater. Having the mask clamped on my head was very distressing at first and it took me a few dives to start feeling OK about that on the surface before a dive. One suggestion a friend made was helpful though, rinsing my face with fresh, cold water before putting the mask on helped a lot to relax me. Apparently this stimulates the mammalian dive reflex? I just know it felt a whole lot better and cooled me down a bit at the same time.

When rescues were performed we were required to wear fins but at other time they were optional. Most people felt they were in the way when working in the cage (lifting pipe work and so forth). I didn't feel I had much control of my position or depth without my fins and this contributed to hurting my ear a bit on one dive because I couldn't swim up properly to control my own depth. Consequently I wore fins on most dives after that.

"Not

here to [expletive deleted] spiders", what about the diving?

"Not

here to [expletive deleted] spiders", what about the diving?

We did 24 dives on the course for predetermined times and depths (to meet requirements specified under AS2815.1). Most of our diving was done off a large barge owned by the NZSCDT, the "Big Pearl". The Big Pearl is set up specifically for SCUBA and surface supply diving with a large generator, compressor, storage banks, cage and winch, diving bell and two large shipping containers to house the recompression chamber, dive gear and control stations.

The water is 60-90 metres deep below the Big Pearl, we worked either off the shore (first 4 dives) or suspended in a cage below the Big Pearl. Vis ranged from zero to 2m and the water temperature was 9-12 degrees (there wasn't much light below about 20 metres). The diving was noisy and very rushed (diver changeovers were meant to take 5-7 minutes including swapping tanks, kiting down, kiting up and pre-dive checks).

On most days we arrived around 8 am at the equipment storage containers on campus and loaded up all personal gear and any additional fuel and equipment we needed onto the "Little Pearl", a smaller barge. We then had a five minute trip to the boat ramp in the back of the truck or barge.

Two of the most stressful days for me on the entire course (OK slightly less

stressful than the exams) were when I acted as assistant supervisor and then

supervisor.  Each day

a different student performed the role of supervisor and it was their job to

make sure we had everything needed for the days diving, oversee the diving operations,

complete most of the paperwork and assign tasks. This was by far the most taxing

job and I was pleased to get it over and done with early.

Each day

a different student performed the role of supervisor and it was their job to

make sure we had everything needed for the days diving, oversee the diving operations,

complete most of the paperwork and assign tasks. This was by far the most taxing

job and I was pleased to get it over and done with early.

Fortunately, I wasn't the first though, that pleasure fell to Andrew, my room mate. I was assistant supervisor on that day which gave me a good introduction to the different personalities and strengths of all the other divers, the different jobs required and the mountain of paperwork. We didn't have to fill out dive plans but there were daily risk assessments (that we needed to convey to all divers and crew), checks for various equipment (introduced gradually), pre-dive check lists, logs for each diver (their profile, tasks, gas use, etc), planning for repetitive diving, paperwork to keep track of everyones progress for the course and so forth.

All this and keeping track of and taking part in all the activity above and

below (diver comms) water. Oh, and we also had to dive at some point.

I think a hall mark of good planning and leadership (for want of a better word)

is identifying peoples strengths and weaknesses and playing to those. In this

context I think as much as possible it was useful to choose the right people

for critical jobs. The days flowed much more smoothly when this was done. It

seemed to me the supervisor could facilitate or hinder the success of a diving

operation. I found this aspect of the course very informative and rewarding.

Launches

and retrievals at the boat ramp were always entertaining (this is where a lot

of the group dynamic came to the front, not always in a good way). Once the

Little Pearl was in the water everyone loaded up and we headed out to the Big

Pearl for someone (usually the supervisor) to play chicken with the electric

fence before setting up the gear for another days diving. On the right: launching

the Little Pearl (always entertaining). Too many chiefs and not enough indians

often made for some chaotic launches and retrievals and the odd harsh word...

Launches

and retrievals at the boat ramp were always entertaining (this is where a lot

of the group dynamic came to the front, not always in a good way). Once the

Little Pearl was in the water everyone loaded up and we headed out to the Big

Pearl for someone (usually the supervisor) to play chicken with the electric

fence before setting up the gear for another days diving. On the right: launching

the Little Pearl (always entertaining). Too many chiefs and not enough indians

often made for some chaotic launches and retrievals and the odd harsh word...

On

the left here, another days diving begins in earnest. Clearly some thought has

gone into the psychology of group dynamics because I really felt like a student

/ newby diver wearing those orange and blue overalls (instructors in yellow)...

On

the left here, another days diving begins in earnest. Clearly some thought has

gone into the psychology of group dynamics because I really felt like a student

/ newby diver wearing those orange and blue overalls (instructors in yellow)...

Diving with a tender was a new experience for me. I found it could be either a positive or negative experience depending on the tender I had and the level of control I felt I had (which depended a bit on how well I could communicate what I needed to the surface, not always easy with so much action topside). The tender performs a very important function and I was told that good tenders are highly prized. Having a shot line and tender is one of the principle differences between the commercial and recreational diver.

The tender has an extremely important role in maintaining the comfort and safety of the diver (this brief summary will not do justice to the job). The tender often sets up the dive equipment (as well as coiling and securing the shot line and setting up comms), they keep the diver comfortable on the surface with food or drink or other needs, they help the diver kit up and perform pre-dive checks, they assist divers in and out of the water, they do a bubble check in the water, they help the diver kit down and in some circumstances control a divers ascent and descent rate and relay instructions to the diver using line signals. Most importantly the tender maintains tension on the shot line and minimises slack (which can entangle divers) while still allowing divers to move around easily at the work site.

In general I found the diving a whole lot less stressful than tendering or

working on the surface in other roles (such as supervisor). My most enjoyable

experiences during the course were doing the zero vis search patterns early

on in the course. The tender controls the process with line signals ("face

shot and turn left", "face shot and turn right", etc) so as a

diver you really just need to move along feeling through the mud for the objects

you're searching for and  responding

to the signals. Having done a large amount of work in zero vis I found this

quite relaxing. Unfortunately, every now and again I'd find what I was

searching for and have to surface.

responding

to the signals. Having done a large amount of work in zero vis I found this

quite relaxing. Unfortunately, every now and again I'd find what I was

searching for and have to surface.

Tenders are not the only ones who need to be aware of the shot line however. Divers also need to be aware of their line and how it is positioned underwater. This became particularly important when we moved off-shore and started diving in a steel cage lowered to depth below the Big Pearl. It was important that divers avoid tangling each other on descent or during a dive. Very easy to do if you start swimming around each other on descent or while working (without being aware of lines crossing). You also need to be aware of where you entered the cage. Divers needed to think about where they would enter the cage so they avoided tangling the lines of other divers and also to make sure that their shot line was as free and unimpeded as possible. It was equally important to exit the cage in the same way you entered and avoid getting tangled in pipe work and other hazards in the cage.

On

the right, Simon K and Craig are ready to hit the water on the Big Pearl. Notice

the big yellow knives in the white sheaths on the left shoulder D-ring. We had

to make our own, needed to be long enough and sharp enough to cut through air

lines (pictured in the background), comm's and hydraulic lines in one motion.

It was stressed however that cutting shot lines was an absolute last resort

(in most cases any problems you can't solve yourself are solved by sending in

the standby diver)...

On

the right, Simon K and Craig are ready to hit the water on the Big Pearl. Notice

the big yellow knives in the white sheaths on the left shoulder D-ring. We had

to make our own, needed to be long enough and sharp enough to cut through air

lines (pictured in the background), comm's and hydraulic lines in one motion.

It was stressed however that cutting shot lines was an absolute last resort

(in most cases any problems you can't solve yourself are solved by sending in

the standby diver)...

As the previous picture shows yes there were people wearing wetsuits. In fact

out of 14 divers on the course (including the RPL guys) less than half used

drysuits. New Zealand divers are a tough bunch. I would not have even contemplated

going in the water without my drysuit.

This

is me, next to the diving bell (used for surface supply diving) on Big Pearl.

"High viz" clothing, steel capped boots and hard hats were the order

of the day. On one dive I looked up to see a massive pipe (must have weighted

several hundred kilo's) swinging back and forth within inches of my head. Definitely

needed your wits about you...

This

is me, next to the diving bell (used for surface supply diving) on Big Pearl.

"High viz" clothing, steel capped boots and hard hats were the order

of the day. On one dive I looked up to see a massive pipe (must have weighted

several hundred kilo's) swinging back and forth within inches of my head. Definitely

needed your wits about you...

I was toasty with two layers of drysuit thermals (400 gram thinsulate and 300 gram polypropylene) but my hands and feet did get rather cold on a few dives. At times I didn't have the strength to disconnect an inflator and after a 90+ minute dive my feet were so numb it took over an hour and a half before I could walk properly or feel my toes.

I had tried to get some dry gloves for the course but on reflection this would

have been impractical. Thick (5mm) wet suit gloves were enough for these conditions

but a lot of the time I needed to dive without them so I could perform tasks

that needed dexterity. Thinner gloves may have come in handy.

This

is me again on the right, ready for a dive. Took me a while to get my weighting

sorted with the extra thermals and unfamiliar fresh water. There was no time

to test out weight or new gear so I did my checkout dive with a rock held between

my knees (about 2-3 kilos light)...

This

is me again on the right, ready for a dive. Took me a while to get my weighting

sorted with the extra thermals and unfamiliar fresh water. There was no time

to test out weight or new gear so I did my checkout dive with a rock held between

my knees (about 2-3 kilos light)...

On the last day of the course they blasted us down to 50m very quickly ("so we definitely got narked"). Felt rather like I was going into space (or perhaps back to the 60's in terms of mental state). Although not my first dive to 50 metres, my first chamber dive. Very funny experience listening to everyones Donald Duck voices (one group in the chamber laughed for the whole 12 minute bottom time). They got us to do various tasks like spelling our names backwards and various maths, several of us complained that we couldn't do the questions on the surface let alone 50 metres.

Definitely a new experience, we deco'd out on pure oxygen using the chambers

BIBS, which stands for Built in Breathing System.

Overall impressions and comments

Overall I felt the course was a positive experience, although I was pleased to get back to Auckland at the end of my four weeks for some decent food and eventually my own kitchen and bed back in Australia.

There are things I felt could be done better and definitely lessons learnt on my part. A lot of new insights and material to help improve the running of the dive operations back at work. I did enjoy the experience though and feel that I was fortunate to have such a great bunch of people to do the course with. Everyone was very generous and friendly.

I definitely felt the instructors knew their stuff and were obviously knowledgeable

and experienced commercial divers. Richie and Allan brought a great deal of

real world experience to their teaching and both were approachable and friendly.

I very much appreciated the way they put up with my constant questions.

The facilities and equipment were in good order and care was taken to fix any

problems before divers entered the water. Allan ordered in any extra personal

gear that we needed and this helped a great deal. Particularly for me as

I didn't have transport and needed to rely on others.

Having said that I think that training materials and techniques are really just developing for commercial training. The instructors are working divers but not necessarily trained educators and I think that these will improve with time. So view the following comments in that context.

I did feel that (despite running for a month) some times we rushed through some material that may have benefitted from further explanation or time to get the process right. We finished a day early, finished early most fridays and occasionally other days so there was time to spare. I would personally have been happy to work at least one day on the weekend if needed but realise most people wouldn't have been prepared to do that. Most locals headed home on the weekend and were champing at the bit to get away from Huntly, can't imagine why :-)

I think at times we needed a much clearer outline of what we needed to do during a dive. For example, when we were first asked to flood a mask how you did this wasn't explained (and with positive pressure masks like the AGA this is very difficult). Also with the hull survey work the difficulty in navigating with rusty hull plates and growth and the noise (making clear communication difficult) required more forethought and planning.

One thing that I try to do when running specialty dives or briefing divers for recreational or scientific dives is run through the dive and each divers role in the sequence the dive will progress. I feel that this helps people visualise the dive in their mind (rehearse if you like). Visualising a task or sequence of tasks has been proven to improve performance.

In my view speed comes with time and the most important thing initially is to get the process (the sequence of events in kitting a diver up for example) committed to memory first, so it is second nature. This can only be done by running through the steps slowly and methodically (reinforcing neural pathways). So that you start off doing it right and don't miss things when the pressure is on.

There were a number of incidences where time was wasted because things had

been forgotten while everyone rushed through their jobs.

On one dive my harness had been left undone, I know I forgot to hook up the

shot line several times before the mask was put on (leaving it dangling and

putting weight on the comms line). We got much more efficient by the end (at

least in my view) but I think a more structured approach early would have helped.

I also feel the course would benefit from a more rigid overall structure. I

realise weather can dictate dive days but this is much less of an issue on a

lake than in the ocean. I know the instructors discuss each days activities,

monitored where everyone was up to and made contingencies as required, but I'd

have liked to have had a timetable and perhaps a closer link between a theory

component and the related practical work. I have also been taught that listing

learning objectives at the start of a lecture or exercise is a good practice

(also a quick overview of what will be covered, how this fits in with the curriculum

and a brief rationale).

I had some reservations about ascent rates on the course and was vocal about this (some of the RPL guys and others commented on this to). Richie made a point of ensuring the ascent rate required under the DCIEM tables (18m/minute) was enforced. Some of the tenders had been a bit over zealous early on, rushing to pull divers up (particularly problematic for us dry suit divers needing to vent suits).

Further, my impression before and during the course was that the commercial industry as a whole is somewhat behind the times on decompression and recent trends with deep stops, use of mixed gasses and slower ascent rates (especially near the surface). Whether this is because they are waiting on larger data sets to highlight trends before introducing new practices I'm not sure. I'd hope it's not just to expedite work and training. There are mechanisms for incorporating what I consider more conservative measures into dives conducted using the DCIEM tables. I don't think the presence of pain or other symptoms or even bubbles in the blood is the whole story with decompression injury and I think practices should evolve with new models and research (not just rely on established practice or models that limit the incidence of overt signs and symptoms).

I hope these last comments have not sounded too negative because as I say I enjoyed the course and the people and learnt a great deal. Hope this article has been informative and you know a little bit more about what to expect out of commercial training.

Shopfront

-

Sea & Sea YS-01 SOLIS Strobe head

Sea & Sea YS-01 SOLIS Strobe head

- Price A$ 739.00

-

Underwater X Elk Draws Stainless Steel Insulated Water Bottle for Mental Health - Whale Shark

Underwater X Elk Draws Stainless Steel Insulated Water Bottle for Mental Health - Whale Shark

- Price A$ 39.95

-

SeaLife - SportDiver ULTRA Pro 2500 Set

SeaLife - SportDiver ULTRA Pro 2500 Set

- Price A$ 1,299.00

-

Nitescuba Tripod Bracket for Underwater Camera Housings

Nitescuba Tripod Bracket for Underwater Camera Housings

- Price A$ 249.95

-

AquaTech EDGE Pro Camera Water Housings - Canon EOS mirrorless

AquaTech EDGE Pro Camera Water Housings - Canon EOS mirrorless

- Price A$ 2,149.00

-

Sea Dragon 2000F Photo/Video Light - GoPro® ready

Sea Dragon 2000F Photo/Video Light - GoPro® ready

- Price A$ 539.00

-

Smart Waterproof Phone Case H1

Smart Waterproof Phone Case H1

- Price A$ 189.00

-

Fotocore M15 Photo Video Light - 15,000 lumens

Fotocore M15 Photo Video Light - 15,000 lumens

- Price A$ 1,399.00

In the Directory