- Home

- Directory

- Shop

- Underwater Cameras - Photographic Accessories

- Smartphone Housings

- Sea Scooters

- Hookah Dive Systems

- Underwater Metal Detectors

- Dive Gear

- Dive Accessories

- Diving DVD & Blu-Ray Discs

- Diving Books

- Underwater Drones

- Drones

- Subscriptions - Magazines

- Protective Cases

- Corrective Lenses

- Dive Wear

- Underwater Membership

- Assistive Technology - NDIS

- On Sale

- Underwater Gift Cards

- Underwater Art

- Power Stations

- Underwater Bargain Bin

- Brands

- 10bar

- AirBuddy

- Akona

- AOI

- Apollo

- AquaTech

- Atomic Aquatics

- aunoc

- AxisGo

- Backscatter Underwater Video and Photo

- BLU3

- Buddy-Watcher

- Cayago

- Chasing

- Cinebags

- Contour

- Deepblue

- Devilite

- Digipower

- DJI

- Dyron

- Edge Smart Drive

- Eneloop

- Energizer

- Exotech Innovations

- Fantasea

- FiiK Elektric Skateboards

- Fotocore

- Garmin

- Geneinno

- GoPro

- Hagul

- Hoverstar

- Hydro Sapiens

- Hydrotac

- Ikelite

- Indigo Industries

- Inon

- Insta360

- Intova

- Isotta Housings

- Jobe

- JOBY

- Kraken Sports

- LEFEET

- Marelux

- Mirage Dive

- Nautica Seascooters

- Nautilus Lifeline

- NautiSmart

- Nitecore

- Nocturnal Lights

- Nokta Makro

- Ocean Guardian

- Oceanic

- Olympus

- OM System

- Orca Torch

- Overboard

- Paralenz

- PowerDive

- QYSEA

- Ratio Dive Computers

- Scubajet

- Scubalamp

- Sea & Sea

- SeaDoo Seascooter

- SeaLife

- Seashell

- Seavu

- Shark Shield

- Sherwood Scuba

- Spare Air

- StickTite

- StormCase

- Sublue

- Suunto

- SwellPro

- T-HOUSING

- Tusa

- U.N Photographics

- Venture Heat

- XTAR

- Yamaha Seascooter

- Youcan Robot

- Zcifi

We all know this: Sharks, not humans, most at risk in ocean

During another summer of media frenzy about shark attacks everywhere it is always good to sit down and put things into perspective. The following article tries to undo ...

Three shark attacks in Australia in two days in the past week sparked a media frenzy, but sharks are more at risk in the ocean than people, with humans killing millions of sharks each year.

Sharks are the top of the marine food chain, a powerful predator which has no match in its watery realm, until humans enter the ocean.

Australia's Shark Research Institute says commercial fishing and a desire for Asian shark fin soup sees up to 100 million sharks, even protected endangered species of sharks, slaughtered around the world each year.

Yet in contrast, sharks do not seem to like the taste of humans. Very few shark attacks involve the shark actually eating the human, unlike a land-based predator like a lion or tiger.

The Shark Research Institute says on its website that most of the incidents in the Florida-based global shark attack file "have nothing to do with predation".

Unlike fat seals - the preferred meal of sharks like the great white - humans are bony with not much fat. Sharks use various sensors to hunt their prey and a quick bite will tell it whether it has found a good meal.

Usually when a shark bites a human it then swims off. Unfortunately for humans, sharks are big and people are small, so a large shark bite can mean death from rapid loss of blood.

"Sharks are opportunistic feeders. They hear us in the water, we sound like a thrashing fish or animal in the water, and they just react to that instinctively and go to take a bite," marine analyst Greg Pickering said on Wednesday.

Australia and Florida

According to the latest figures by the global shark attack file, there was only one fatal shark attack in 2007. It took place in New Caledonia in the South Pacific. The mean number of deaths between 2000 and 2007 was five a year.

"You have more chance of being killed driving to the beach," said John West, the curator of the Australian shark attack file at Sydney's Taronga Zoo.

In fact, the number of fatal attacks around the world has been falling during the 20th century, due to advances in beach safety, medical treatment and public awareness of shark habitats.

The bulk of shark attacks do not happen in Australian waters, despite its shark reputation, but in North American waters. Half of the world's shark attacks occur in the United States, and one third of the world's attacks are in Florida waters.

In 2007, there were 50 shark attacks in US waters, compared with 13 in Australia in the same year. None were fatal.

The big difference between Florida and Australia is that Australia has much bigger sharks and therefore more fatal attacks. From 1990 to 2007, Australia had 19 fatal attacks, Florida only four.

The Australian shark attack file says there has been a total of 56 fatal shark attacks in Australia in the past 50 years, or an average of about one a year.

The last fatal attack occurred in December 2008, when a great white shark attacked a 51-year-old man while he was snorkelling off a beach south of Perth in Western Australia.

So, is it safe to go back in the water?

Shark attacks are on the rise worldwide, but according to the international shark attack file, that doesn't mean there is an increased rate of shark attacks.

The file on its website that as the world population increases and interest in aquatic recreation rises, "we realistically should expect increases in the number of shark attacks".

Sharks in decline

But while more humans enter the ocean each year and for longer periods of time, the shark population is declining, theoretically reducing the chances of a shark-human encounter.

"As a result, short-term trends in the number of shark attacks, up or down, must be viewed with caution," says the file.

So, if shark numbers are falling, why are there more sightings of sharks off Australia's beaches? Surfwatch Australia, which conducts aerial patrols of Sydney beaches, estimates shark sightings have risen 50 to 80 per cent in recent years.

Wildlife officials say cleaner beach water means sharks are chasing food closer to shore. Sydney beaches were closed this month when hammerheads started feeding on squid near swimmers.

But only about two dozen shark species are considered potentially dangerous to humans because of their size and teeth.

The great white, bull, tiger and hammerhead sharks are among the most aggressive and responsible for most attacks in Australia.

Great whites can grow to 5.5 metres in length, weigh up to 1,000 kilograms and have the biting power to lift a car.

Australian scientists have recorded the bite power of a 3.2-metre shark as equivalent to 1.5 tonnes of pressure.

The aggressive-looking grey nurse shark, with its piercing eyes, pointy nose and protruding teeth, is as timid as a cat and will only attack if provoked.

But its fierce appearance has seen it hunted to the point where it is now endangered and colonies of grey nurse sharks off Sydney are protected.

There are 30 sharks, including the great white, on the International Union for Conservation of Nature's threatened species list.

Australia's Nature Conservation Council has launched a 'Save Our Last Sharks' campaign.

"Sharks need our help now and we cannot let our fear push them to the brink of extinction," says the Council's Ben Birt.

from the ABC: http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2009/01/17/2468318.htm

![]() Contributed by Tim Hochgrebe added 2009-01-17

Contributed by Tim Hochgrebe added 2009-01-17

Replies of 1

-

Tim Hochgrebe added 2009-01-17

Tim Hochgrebe added 2009-01-17

More news like that now from the Sydney Morning Herald

http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/its-safe-to-go-into-the-water/2009/01/17/1231609053569.html

Replies of 1

![]() Login or become a member to join in with this discussion.

Login or become a member to join in with this discussion.

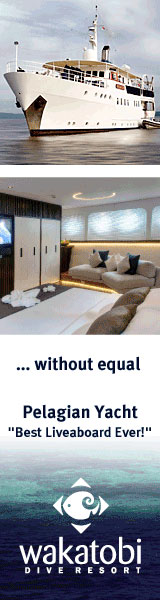

Wakatobi Dive Resort

Wakatobi Dive Resort

Wakatobi Dive Resort has some of the most pristine reefs in Indonesia at its doorstep. Protected by their Collaborative Reef Conservation Program, Wakatobi is the #1 choice for sophisticated divers.

Shopfront

-

Sublue Tini - Modular Underwater Scooter

Sublue Tini - Modular Underwater Scooter

- Price A$ 799.00

-

FLIP12 Pro Package with DIVE & DEEP Filters & +15 MacroMate Mini Lens for GoPro HERO 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13

FLIP12 Pro Package with DIVE & DEEP Filters & +15 MacroMate Mini Lens for GoPro HERO 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13

- Price A$ 339.00

-

AquaTech EDGE Pro Camera Water Housings - Canon EOS mirrorless

AquaTech EDGE Pro Camera Water Housings - Canon EOS mirrorless

- Price A$ 1,849.00

-

CineBags - CB23 DSLR Backpack

CineBags - CB23 DSLR Backpack

- Price A$ 405.95

-

Isotta Underwater dSLR Camera Housings

Isotta Underwater dSLR Camera Housings

- Price A$ 4,899.00

-

AquaTech EDGE PRO Conversion Kit - Sony - Nikon - Canon - Fuji

AquaTech EDGE PRO Conversion Kit - Sony - Nikon - Canon - Fuji

- Price A$ 1,049.00

-

Kraken Hydra 6000 WRGBU

Kraken Hydra 6000 WRGBU

- Price A$ 949.00

-

Sea Dragon 2000F Photo/Video Light - GoPro® ready

Sea Dragon 2000F Photo/Video Light - GoPro® ready

- Price A$ 539.00

Articles

-

The Dragon Seamoth

The Dragon Seamoth

by Allister Lee

- We saw the Dragon Sea Moth (Eurypegasus draconis) at a dive site at Mabul Island. Ribbon Valley to be exact. I took a few shots of this cool little fish a week ago and it is still around now.